By Khurram Ali Shafique

Man is enslaved neither by his race nor by his religion, nor by the course of rivers, nor by the direction of mountain ranges. A great aggregation of men, sane of mind and warm of heart, creates a moral consciousness which is called a nation. (Ernest Renan, quoted by Iqbal in the Allahabad Address)

Ernest Renan (1823-1892) was a French Orientalist who was regarded highly until the Second World War. Since then, he seems to have fallen out of favor with the academia. Still, his principle of nationalism is so powerful that modern students of social sciences find it impossible to ignore it completely, in spite of their reluctance to consider it for application. Curiously enough, there is a connection between him and Iqbal and it is one that makes them indispensable to each other. Renan's passionate plea, which he made in the "Introduction" to his Collected Speeches in 1887, can take a completely new meaning if we read it in the light of Iqbal Studies. Renan had referred to his 1882 lecture "What Is A Nation?", and had said:

"I hope that these twenty pages will be recalled when modern civilization flounders as a result of the disastrous ambiguity of the words: nation, nationality, race."

Those "twenty pages", which Renan had hoped would save the world, became the intellectual premise for Iqbal's proposal about the birth of a new state. In his Allahabad Address, Iqbal quoted from this lecture of Renan in a manner which makes his own writing – also comprising of some twenty pages – a sequel to Renan's lecture, and could easily be subtitled "What Is A Nation? Part 2". Hence, the passionate warning of Renan that his lecture should be used for averting disasters may now be seen as directly addressed to Pakistanis (and by that implication to Bengalis and Indians in so far as the creation of Pakistan is a fact of their history too). They people cannot afford to disregard the warning of Renan even if the rest of the world forgets him. In their history, those twenty pages have played an actively role unlike anywhere else in the world. The key for understanding this is to consider three crucial references to Renan in the writings of Iqbal.

An independent critical attitude

An independent critical attitude

"Our duty is carefully to watch the progress of human thought, and to maintain an independent critical attitude towards it." This is the advice which Iqbal offered to his readers at a certain stage, and it reflected a practice which he had followed throughout. A very good example of this "independent critical attitude" is his engagement with the thought of Renan.

Renan was a confirmed racist who believed colored races to be inferior and possibly unfit for self-rule. He also had serious disagreement with the Christian Church. His writings also concealed a hostility towards Islam (which did not go unnoticed by Iqbal). Yet, one of the notes which Iqbal jotted down in his private notebook, apparently as a reminder to himself, was about the need to see beyond such observations:

There are some people who are sceptical and yet of a religious turn of mind. The French Orientalist Renan reveals the essentially religious character of his mind in spite of his scepticism. We must be careful in forming our opinion about the character of men from their habits of thought. (Stray Reflections, p.73)

The benefit of this approach becomes evident when we look at how it helped Iqbal to engage with the powerful mind of Renan in a creative and original manner as we shall see now.

Religion as a people-building force

In his 1882 paper, Renan had shown conclusively that geography, race, language or religion did not make a nation. About Islam, he had written somewhere that it was going to "lose the high intellectual and moral direction of an important part of the universe". Quoting this statement in his paper "The Muslim Community" (1911), Iqbal called it "a veiled hope" on Renan's part that Islam should thus fizzle out.

Yet he bypassed such quibbles and managed to meet Renan on the grounds of common principles. The first principle which Iqbal seems to have discerned from the writings of Renan was that any community, society or nation which hoped to hold itself together merely through belief in certain propositions of a metaphysical import was indeed standing on an extremely unsafe basis, especially before the advance of modern knowledge, with its habits of rationalism and criticism. (Iqbal, "The Muslim Community").

Acceptance of this empirical truth did not deter Iqbal from pursuing that new orientation of Islam which was gradually evolving in Muslim India: "Islam has a far deeper significance for us than merely religious." (Iqbal, "The Muslim Community"). This was the sum total of the cultural activities of the Indian Muslims since 1867 as well as of their social activism, their daily reality and their most valuable intellectual output, including the writings of Sir Syed Ahmad Khan, Syed Amir Ali, Maulana Shibli Numani – not to forget the poetry of Maulana Hali and Akbar Allahabadi, and the writings of young journalists like Muhammad Ali Jauhar and Zafar Ali Khan. The same collective will had also manifested in the recently formed All-India Muslim League, although the significance of that political organization was yet to be tested by history. Consequently, Iqbal made the very far-sighted proposition that the unity of religious belief in the Muslim community was supplemented by the uniformity of Muslim culture:

Mere belief in the Islamic principle, though exceedingly important, is not sufficient. In order to participate in the life of the communal self, the individual mind must undergo a complete transformation, and this transformation is secured, externally by the institutions of Islam, and internally by that uniform culture which the intellectual energy of our forefathers has produced.

Renan had described the evolution of modern European nations to show that diverse factors had gone into their making. Iqbal showed that in Asia, such factors had been provided by Islam, which had been working as much more than a religion. The vision of Islam which he offered was neither a set of metaphysical beliefs nor a two-dimensional study of "lived religion", but was through and through a people-building force (see "The Muslim Community").

This is important because Iqbal made a clear distinction between two very different roles of religion in a society. The first is what Renan had called "the absolute distinction between men in terms of their religion", and had shown to be inadequate for making a nation. Iqbal gave an implicit assent to this by stating, "Mere belief in the Islamic principle, though exceedingly important, is not sufficient," but he made an exception for religion as "a people-building force" – a phenomenon which Renan may not have realized because it was not manifested as clearly in Islam outside India as it did in Islam in India (and Renan was an authority mainly on the Middle East). As Iqbal was going to state very boldly in the Allahabad Address:

Indeed it is no exaggeration to say that India is perhaps the only country in the world where Islam, as a people-building force, has worked at its best.

This subtlety is obviously ignored by those who seek to reinforce the Islamic identity of Muslim societies in South Asia by introducing more rigid models of Islam from other parts of the Muslim world. It also seems to be forgotten by those who hope to make these societies more tolerant and enlightened by importing esoteric and metaphysical wisdom from abroad. At least in the case of Pakistan, this observation is also being ignored by those who propose to impose unpopular secularist oligarchies. All these reformers and adventurers would perhaps benefit by considering what Iqbal stated elsewhere: "The flame of life cannot be borrowed from others; it must be kindled in the temple of one’s own soul. This requires earnest preparation and a relatively permanent programme." (The Lahore Address, 1932).

The most interesting aspect of the connection between Renan and Iqbal is that it helps us restore Renan's principle of nationalism as a workable solution not only in Iqbal's society but perhaps also elsewhere in the world, and points in the direction of that empirical evidence which may qualify Renan's principle for being called, truly, "the spiritual principle of nationalism."

The spiritual principle of nationalism

We have seen that Renan, in his 1882 lecture, had refuted the presumptions of some earlier thinkers that nations could be formed on the basis of geography, race or language. This should be of special interest to the learners of Iqbal Studies, who very well know that Iqbal launched an ideological attack against these theories of nationalism, but most of them do not realize that Iqbal did so on a premise already established for him by another great thinker.

We have seen that Renan, in his 1882 lecture, had refuted the presumptions of some earlier thinkers that nations could be formed on the basis of geography, race or language. This should be of special interest to the learners of Iqbal Studies, who very well know that Iqbal launched an ideological attack against these theories of nationalism, but most of them do not realize that Iqbal did so on a premise already established for him by another great thinker.

We have also seen that Renan's assumption that religion could not provide a feasible basis for nation-building was modified by Iqbal on the grounds that this could be true about a certain conception of religion but not about another conception that was most peculiarly evidenced among the Muslims of India.

Now we may come to consider the question that if geography, race, language or "absolute distinction between men on the basis of religion" does not define a nation, then what does? The answer which Renan provided was the spiritual principle of nationalism. It had two postulates. The first explained how modern nations were formed. The second answered how they could be sustained.

What makes a nation?

Renan claimed that it was an empirically verifiable fact that a modern nation was formed on the basis of two things:

- To have performed great deeds together; and

- To wish to perform still more.

To form a nation on any other basis – even on the basis of an "absolute distinction between men on the basis of religion" – would mean disregarding the consent of the individual, and hence a negation of free will and soul, and would fail. In the words of Renan:

A nation is a soul, a spiritual principle. Two things, which in truth are but one, constitute this soul or spiritual principle. One lies in the past, one in the present. One is the possession in common of a rich legacy of memories; the other is present-day consent, the desire to live together, the will to perpetuate the value of the heritage that one has received in an undivided form. Man, Gentlemen, does not improvise. The nation, like the individual, is the culmination of a long past of endeavours, sacrifice, and devotion. Of all cults, that of the ancestors is the most legitimate, for the ancestors have made us what we are. A heroic past, great men, glory (by which I understand genuine glory), this is the social capital upon which one bases a national idea. To have common glories in the past and to have a common will in the present; to have performed great deeds together, to wish to perform still more—these are the essential conditions for being a people.

What sustains a nation?

Once we accept that nations are founded on the basis of will, it follows naturally that they can only be sustained through consent, whether obtained implicitly or explicitly:

A nation's existence is, if you will pardon the metaphor, a daily plebiscite, just as an individual's existence is a perpetual affirmation of life. That, I know full well, is less metaphysical than divine right and less brutal than so called historical right. According to the ideas that I am outlining to you, a nation has no more right than a king does to say to a province: "You belong to me, I am seizing you." A province, as far as I am concerned, is its inhabitants; if anyone has the right to be consulted in such an affair, it is the inhabitant. A nation never has any real interest in annexing or holding on to a country against its will. The wish of nations is, all in all, the sole legitimate criterion, the one to which one must always return.

The Allahabad Address

This was the principle which Iqbal invoked while delivering his presidential address to the All-India Muslim League at Allahabad in December 1930. At that hour, when civilization was indeed floundering as a result of the disastrous ambiguity of the words nation, nationality, race, Iqbal may have been the only one, perhaps in the whole world, to actually turn to those twenty pages of Renan (among other things), as he stated:

“Man,” says Renan, “is enslaved neither by his race nor by his religion, nor by the course of rivers, nor by the direction of mountain ranges. A great aggregation of men, sane of mind and warm of heart, creates a moral consciousness which is called a nation.” Such a formation is quite possible, though it involves the long and arduous process of practically re-making men and furnishing them with a fresh emotional equipment. It might have been a fact in India if the teachings of Kabir and the Divine Faith of Akbar had seized the imagination of the masses of this country. Experience, however, shows that the various caste units and religious units in India have shown no inclination to sink their respective individualities in a larger whole. Each group is intensely jealous of its collective existence. The formation of the kind of moral consciousness which constitutes the essence of a nation in Renan’s sense demands a price which the peoples of India are not prepared to pay.

|

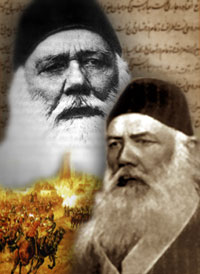

| "If doubts arise regarding its frontiers, consult the populations in the areas under dispute." Only one of the men in this picture could have felt happy that Renan had said such a thing. |

Conclusion

Renan did not offer his proposition as "a theory". He propounded it as an empirical principle and challenged his detractors to put it to empirical test. He was also aware that his European contemporaries were likely to discard his principle as "a fine example of those wretched French ideas which claim to replace diplomacy and war by childishly simple methods." Ruefully, he observed:

This recommendation will bring a smile to the lips of the transcendants of politics, these infallible beings who spend their lives deceiving themselves and who, from the height of their superior principles, take pity upon our mundane concerns.

It could be very rewarding to apply Renan's principle to a case study of the history of South Asia from 1887, and see what empirical evidence turns up. For this, we shall need to add the twenty pages of the Allahabad Address to the original twenty of Renan's What Is A Nation. Such a study has not been undertaken until now and still awaits some insightful and bold scholar.

Further reading

- Essential excerpt from English translation of Renan's paper "What Is a Nation?"

- Complete English translation of the paper

- Iqbal's Allahabad Address

- 'The Uniformity of Muslim Culture' in Iqbal: His Life and Our Times (2014) by Khurram Ali Shafique